Free Flight Design Specifications and Performance

Planes soaring gracefully through the sky have astonished me for as long as I can remember. Eventually, I was made aware about indoor free-flight competitions by my high school engineering teacher, Mr. Travis Hodges. To compete, competitors construct balsa-based rubber-band powered planes that sustain flight for extended periods of time. Depending on the competition, limitations are placed on the plane's mass, rubber's mass, fuselage's length, and wingspan.

First Competition

The video above shows my first plane at my first free flight competition with the Technology Student Association. In this competition, the plane must weigh a minimum of 8 grams, fit in a 35cm x 40cm x 25cm box, and consist of rubber weighing less than 8 grams. Additionally, the judges award a bonus for taking off from the ground and landing on the ground with the landing gear.

Documentation

Between 2018 and 2021, I accumulated several awards in free flight competitions conducted by organizations such as the Technology Student Association (TSA) and Science Olympiad. The documentation above is my final competition plane's memory before COVID-19 consumed people's thoughts.

Final Flight

Over the years, I learned several tips and techniques for constructing and flying a plane. Techniques range from using flow simulations on SolidWorks to perfecting the airfoil's shape during construction to treating the rubber with lubricants to slow the loading rate. My final recorded flight before COVID-19 is shown above. Unfortunately, several conditions, including but not limited to the ambient temperature, downward drafts from vents, and damages to the plane during transportation, limited the plane's peak flight time. However, the highest recorded free flight time was 2:42 (minutes:seconds).

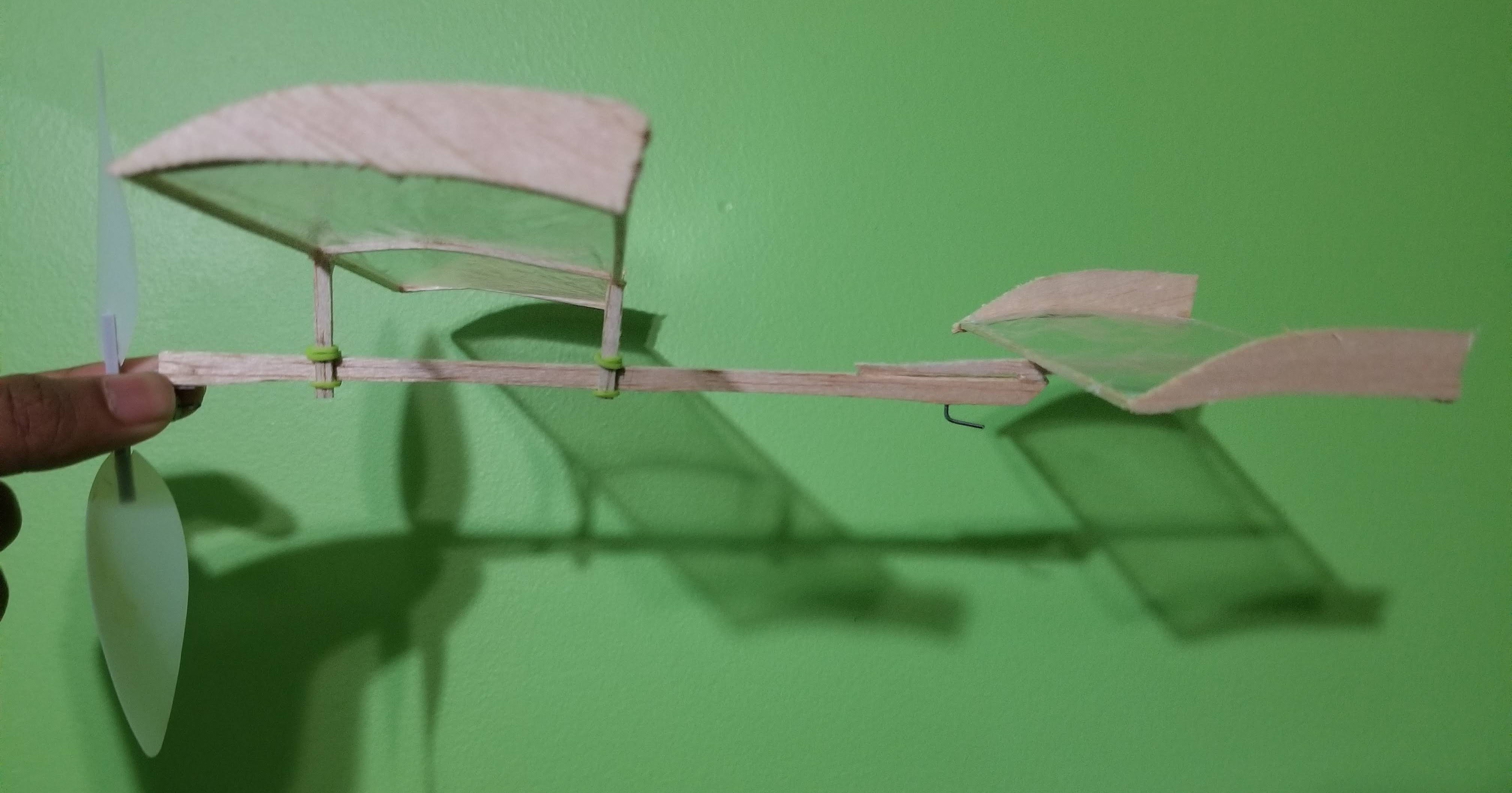

Indoor Design

Unable to stop building planes, I had begun constructing smaller planes designed to fly in my small bedroom. The primary challenge was to generate the necessary centripetal force to minimize its path's radius. Ultimately, I was able to construct this 3.5-gram plane with a custom-designed propeller during quarantine.